As is often repeated, cells are the basic building blocks of all life. They are responsible for generating the energy that sustains life, eliminating waste, and replicating to replace damaged tissues. From single-celled organisms to humans, complex function is possible because of cells and the flexible functions of their parts.

Bacteria: Basic but Capable

Some organisms consist of a single cell, with only the most basic components. They contain genetic material (DNA), ribosomes, cytoplasm, and a cell membrane. Bacteria, for example, mainly consist of these most basic parts of a cell, and sometimes also a cell wall. Yet bacteria are capable of causing human illnesses, from mild food poisoning to deadly tuberculosis. Conversely, they are also capable of promoting human health; for example, bacteria living in the human gut aid in digestion and nutrient absorption, among other things.

Due to the dynamic capabilities of their limited cell parts, bacteria are also able to form biofilms. A biofilm is a layer of microbes held together by a protective film of secreted, or released, molecules. The secretory capabilities and properties of the bacterial cell membrane, including cell surface structures, such as proteins and flagella, contribute to bacteria's ability to form biofilms. Some biofilms are harmful and may grow on medical equipment and cause infection. They also form on industrial materials, such as oil and gas pipelines. Biofilm-associated corrosion of these materials accounts for 20 percent of total corrosion damages, costing billions of U.S. dollars to prevent and fix. This type of corrosion may even result in environmental damages from pipeline leaks.

Genetic material has the ability to exist in mobile segments. This allows bacteria to exchange portions of DNA through a process called horizontal gene transfer. Unlike vertical gene transfer, which occurs when parents pass on DNA to their offspring, horizontal gene transfer involves genetic material moving from one living organism to another, regardless of relatedness. This capability allows the rapid spread of antibiotic resistance in bacteria. Horizontal gene transfer is more common in prokaryotic organisms, such as bacteria, because they lack a nuclear membrane that protects an organism's genetic material from foreign DNA.

Yeast and Slime Molds

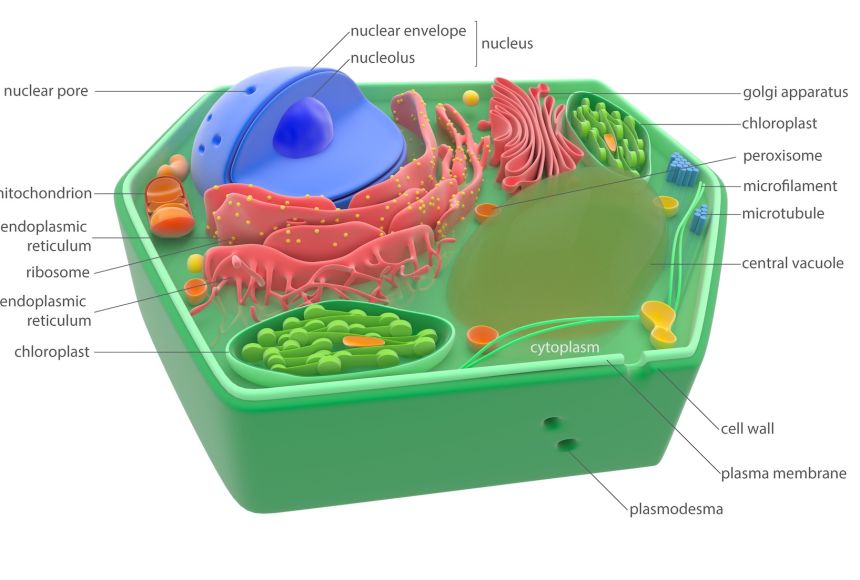

More complex single-celled organisms, such as yeast, are eukaryotic. Unlike prokaryotic cells, eukaryotic cells contain a nucleus as well as other organelles. Organelles are like the cell's organs, in that they are cell parts that perform specific sets of tasks. The organelles in yeast allow it to perform processes like fermentation, which humans have harnessed for our use and enjoyment in making bread, wine, beer, and even biofuel. Fermentation is possible because of certain enzymes within yeast that allow it to convert sugars into alcohol. Enzymes are proteins, and, like all proteins, they are produced by ribosomes within a cell.

Other single-celled organisms, such as cellular slime molds, a type of amoeba, can aggregate to form a multicellular structure. These social amoebas will function as individual organisms when soil nutrients are present. In times of low nutrients, however, they band together to migrate in a slug-like form to search for food. The cellular communication between amoebas during aggregation involves many cell parts, including the cytoskeleton and the nuclear membrane. In this case, the nuclear membrane controls the entry of key molecules from the cytoplasm into the nucleus. In here, these molecules regulate gene transcription, or copying—the first stage of gene expression.

Ultimately, the aggregate amoeba typically differentiates into stalk cells and spore cells. A large vacuole—that is, an empty space—forms within stalk cells as they undergo cell death and form a column. This process lifts up the spore cells and then scatters them to a new location. Many cell parts play a role in this complex behavior of social amoebas, including functions of the mitochondria. These are critical to cell movement, differentiation and patterning of cells within the multicellular slug.

Complex Organisms: Specialized Cells

In true multicellular organisms, a variety of organelles allow equally incredible feats. Chloroplasts in plant cells allow the organism to capture the sun's energy and produce food. In a growing animal, the cytoskeleton sorts critical parts and molecules within the cell. In doing this, it defines the ends of the cells to enable specific functions as an embryo progresses to a developed organism.

Following development, specialized cells within multicellular organisms perform specific functions in support of the body. Meanwhile, diverse organelles contribute to the ability of cells to accomplish vital tasks. For example, mature red blood cells in mammals lack a nucleus. They want to clear out as much cellular space as possible for a protein called hemoglobin, which allows the cell to carry oxygen from the lungs to the rest of the body. White blood cells are part of the body's immune system. They use lysosomes to engulf and destroy bacteria, preventing infection.

In another example, neurons in the human brain allow problem solving, memory, and emotion. A neuron's cell parts are critical to these functions. Neurons secrete neurotransmitters in response to environmental signals, and this secretion is regulated by organelles called Golgi bodies. These organelles are capable of making special vesicles, or sacs, to transport neurotransmitters outside the neuron, where they aid in cell communication to help regulate things like mood. A long axon fiber extends from the cell and releases these critical signaling chemicals. Then, a neighboring cell's many fingerlike dendrites receive the signals. Internal and external cell structures work together to execute cell-level functions.