The United States Civil War lasted four years and was the bloodiest war in American history. More than 50 major battles were fought on American soil. Below, in chronological order, are five of the most significant battles that took place.

First Bull Run (July 21, 1861)

The first Battle of Bull Run (also called the first Battle of Manassas) was the first major land battle of the Civil War.

Following President Abraham Lincoln's orders, the Union Army under General Irvin McDonnell marched from Washington, D.C., to seize the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Approximately 42 kilometers (25 miles) into the march, his path was blocked by the Confederate Army under the command of General P.G.T. Beauregard.

At first, it seemed as if the Union Army would prevail, but as the battle raged throughout the morning, the Confederates held their ground. Once the Confederate Army received reinforcements early that afternoon, their counteroffensive defeated the Union troops.

The retreating Union troops left the route to Washington, D.C., wide open, however, the Confederates were not able to pursue. Even though combined casualties were relatively few (around 4,800) as a result of the battle, the North realized that they were in for a long, bitter war.

Shiloh (April 6–7, 1862)

By February 1862, the Union Army had achieved victories in central Kentucky and Tennessee. The army planned to move south and capture an important Confederate east-west railway hub in northern Mississippi. To defend the hub, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston fortified the town of Corinth, Mississippi. The Union planned to unite two armies—under Ulysses S. Grant and Don Carlos Buell—and then take Corinth.

Grant's army arrived first and set up a camp in the town of Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, near the Shiloh Meeting House. Johnston planned to strike Grant's army before Buell arrived, and at dawn on the sixth of April, Johnston's forces attacked. Grant's Union forces were surprised but remained in the field after a day of fierce fighting. Buell's forces finally arrived overnight, and the combined Union force attacked at dawn. Beauregard—the new Confederate general, after Johnston was mortally wounded—withdrew.

The battle resulted in combined casualties of more than 23,000 people.

Antietam (September 17, 1862)

Confederate General Robert E. Lee had decided to take the war to the North. He devised a plan to split his army and take supplies in Maryland, move into Pennsylvania, and threaten Washington, D.C. His plans fell into Union hands, and the Union Army marched to confront the force he commanded at Antietam Creek, in northern Maryland. However, the Union General McClellan, known for his cautious approach to engaging in battle, responded tentatively, waiting 18 hours before moving his troops. This gave the Confederates time to bring in reinforcements.

The day ended in a draw, with 23,000 men killed, but halted Lee's plans to invade the North for the time being. Although Lincoln was furious that McClellan allowed Lee to escape, he used the occasion to announce the Emancipation Proclamation.

Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863)

Although Antietam was a setback to Lee's plans, the Union failed to capitalize on it. Lincoln replaced McClellan, but his new generals lost decisively at Fredericksburg, Virginia (December 13, 1862), and Chancellorsville, Virginia (April 30–May 4, 1863). These Confederate victories encouraged Lee to renew his plan to invade the North.

Lee moved the Army of Northern Virginia north, and the new Union General, George Meade, shadowed him to protect Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; and Washington, D.C. The forces met at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, on the morning of the first of July.

Despite early successes, the Confederate forces were not able to drive the Union Army off their position. The following day, as reinforcements arrived for both sides, Lee again failed to dislodge the Union Army.

The third of July saw one last push from the Confederates. Lee ordered what has become known as the Pickett's Charge—an assault of some 15,000 Confederate troops—up Cemetery Ridge. Although the charge broke through Union lines, the Confederates were unable to consolidate their gains and retreated.

Lee prepared for the counterattack he expected the next day, but it never came. He withdrew his forces on the fourth of July, and the Union Army did not pursue. While Meade won the battle and stopped the invasion, he failed to destroy Lee's army and put an end to the rebellion.

Union casualties numbered around 23,000, while Confederate casualties numbered around 28,000.

Lincoln delivered the famous Gettysburg Address at the dedication of the military cemetery later that fall.

Vicksburg (May 22–July 4, 1863)

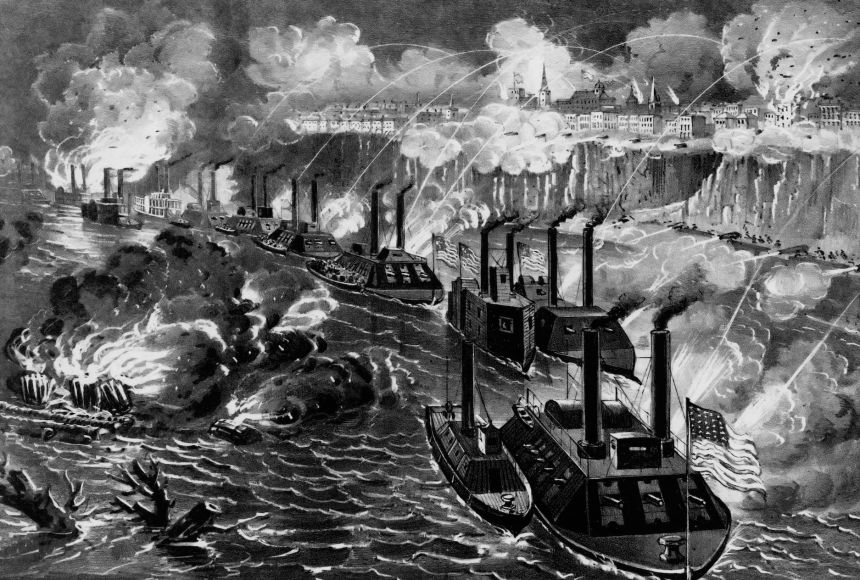

Vicksburg, Mississippi, lies on the east bank of the Mississippi River, about halfway between Memphis, Tennessee, to the north and New Orleans, Louisiana, to the south. Capturing it would give control of the entirety of the Mississippi to the Union. But the city, located on a bluff overlooking the river, was heavily defended with trenches, gun batteries, and a Confederate Army led by General John C. Pemberton.

In May, Union General Ulysses S. Grant led an army south on the west side of the Mississippi past Vicksburg, then crossed over and led his troops back north to lay siege to the city. By mid-June, the Confederates were running low on supplies. General Pemberton surrendered on the fourth of July.

The victories—a day apart—at Gettysburg and Vicksburg marked the turning point of the Civil War. They also ensured that European powers did not recognize the Confederacy as a sovereign nation, withholding much-needed support.

The Civil War killed hundreds of thousands and scarred the countryside. These are just some of the war's major battles. Today, many battlefield sites have been set aside as national parks.