With the highly efficient, organized nature of modern farming, it can be difficult to envision a world where agriculture was an innovative new technology. Yet, 10,000 to 15,000 years ago, during the Neolithic Age, new agricultural communities in Mesopotamia (in southwest Asia), northern Africa, China, and South America began tending the roots of farming as we know it today. Those early steps toward agriculture helped stabilize populations and allow them to grow—a significant change from the nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes of the earlier era.

Farming in the Fertile Crescent

Although it is difficult to pinpoint the exact time when agriculture began to take root, anthropological and archaeological finds suggest that Mesopotamia and parts of northern Africa were among the first civilizations to grow crops. Just like there is no single “birthplace” of agriculture, there is also no single event that triggered the change from mostly hunting to mostly farming. Scientists believe it was likely due to a combination of local factors that linked individual farmers to small populations, which grew into larger agricultural communities. Remarkably, agriculture developed around the same time in several different regions around the world, with no known communication between the societies. One reason for this simultaneous push may include local climate change, a post–Ice Age development that created more favorable conditions for settlement and farming.

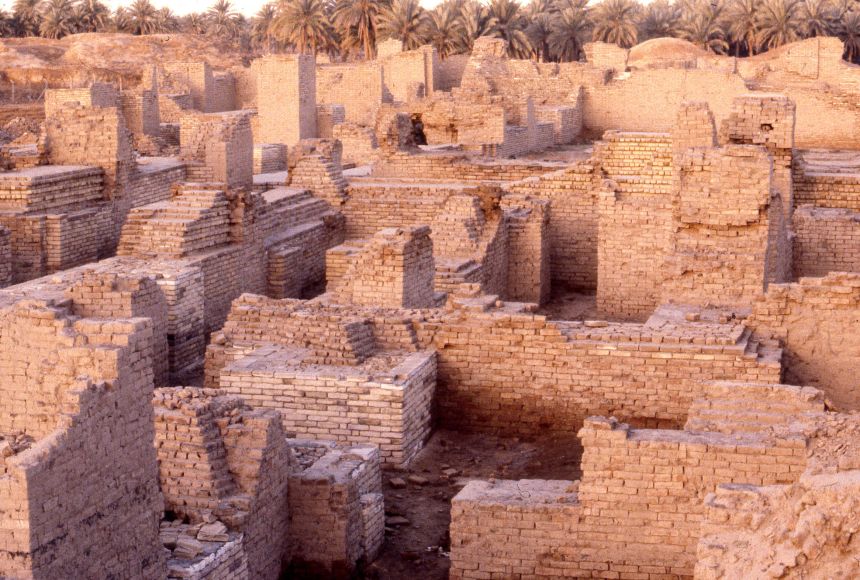

In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians were one of the earliest civilizations to move from hunting and gathering to agriculture for sustenance. With the region’s hot, dry climate, one of the first challenges for early farmers was finding a method to bring water to the crops. The Sumerians built on Egyptian technology and developed an advanced irrigation system for farming. They used ditches, canals, channels, dikes, weirs, and reservoirs to transport water to crops. The Sumerians initially grew wheat as one of their primary crops. Then, when the land accumulated more salt from flooding, draining, and evaporation through the irrigation system, they gravitated toward more salt-tolerant crops like barley instead.

In the same region, another early farming community was Ain Ghazal, a Neolithic settlement located near what is now Amman, Jordan. Although the people of Ain Ghazal are now well-known for their early pottery and burial statues, they may be best remembered for growing crops like barley, wheat, chickpeas, and lentils, and for maintaining herds of domesticated animals.

Early Agriculture in Ancient China

Archaeological data from the Neolithic period shows that Middle Eastern civilizations were not the only ones independently moving toward an agricultural base. In the Far East, agriculture was developing independently of the growth of agriculture in Mesopotamia. One of the earliest known agricultural communities in China was the Yangshao people, whose nomadic hunter-gatherers began to organize into more permanent villages near what is now the Chinese city of Xi’an.

By around 9000 B.C.E., settlements in modern-day China and Mongolia were growing a range of subsistence crops. North of the Qin Mountains, farmers grew mostly wheat and millet. In the south, they cultivated rice. Settling close to rivers, such as the Huang He (Yellow River) basin, resolved many of the water issues that had to be addressed with complex irrigation systems elsewhere. Thus, agricultural communities flourished throughout the region. In addition to rice, the early Chinese farmers branched out into crops like tea, soybeans, millet, peaches, persimmons, hemp, and water chestnuts.

Their work in domesticating a broad range of plants and animals also led to one of the most significant developments to emerge from this era of Chinese agriculture: the silkworm. Silk production and trade would come to define much of the region’s economy and culture in later centuries. Archaeological finds suggest the Yangshao practiced a very early form of silkworm cultivation (also known as sericulture) and silk production.

Agricultural Development in the West

At the same time agriculture was emerging in the East, Neolithic civilizations in South America were evolving toward agriculture as well. Archaeologists found evidence South American civilizations were growing potatoes (which later became a staple crop throughout the Western hemisphere) approximately 10,000 years ago.

The Chavin civilizations, which sprung up in the Andes mountain region of South America, have provided some of the best-preserved archaeological evidence of these early agricultural pioneers. Plant and seed remains were found in caves and other high-elevation rock structures in that region. Early forms of lima beans, squash, and peanuts have all been traced to these Andean farmers. To compensate for steep, rocky land, these highland dwellers also developed the farming method known as terracing, or flattening land to limit erosion and enable irrigation of crops. This process allowed agricultural communities to branch out from the more traditionally fertile lowland river areas.

Throughout the world, this “Neolithic revolution” helped ground communities, and laid the foundation for the cities, towns, and economic growth that would shape the globe as we know it.