This activity is part of a sequence of activities in the What Is the Future of Earth's Climate? lesson. The activities work best if used in sequence.

Preparation

- Required Technology: internet access; 1 computer per learner, 1 computer per small group; interactive whiteboard; projector

- Physical Space: classroom; computer lab; media center/library

- Groupings: heterogeneous grouping; homogeneous grouping; large-group instruction; small-group instruction

Overview

Earth's climate is continually changing. Earth has been covered in ice (snowball Earth) at some points during its existence, while at others, Earth has been ice-free. Earth is now in a warming period, due in part to enhanced human emissions of greenhouse gases. (Greenhouse gases, such as carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor, trap heat in the atmosphere by absorbing heat energy emitted from the surface.)

Scientists use past and current temperature data to develop climate models to predict how warm the planet might get. Scientists use ancient sediments and ice cores to measure past temperatures. They put these data into sophisticated computational models to make predictions about the future.

Learning Objectives

In this activity, students will:

- explore and critically analyze real-world data

- make claims about data and determine their own level of certainty with regard to their claims

Teaching Approach: learning-for-use

Teaching Methods: discussions; multimedia instruction; self-paced learning; visual instruction; writing

Skills Summary

This activity targets the following skills:

- 21st Century Student Outcomes

- 21st Century Themes

- Critical Thinking Skills

- Analyzing, Evaluating, Understanding

Directions

1. Activate students' prior knowledge about Earth's climates.

Tell students that climate is the average weather of a region over a long period of time and that there are many different climates on Earth today. Ask:

- What are some examples of climates? (Some commonly known climates are desert, rain forest, tropical monsoon, tropical savanna, humid subtropical, humid continental, oceanic, subarctic, and tundra.)

- What factors determine a region's climate? (Climate determining factors are location—next to an ocean or near the equator, for example—precipitation, and temperature.)

Tell students that climate scientists use the average temperature of Earth as a measure of climate change. Ask: Has Earth always had the same climates as it has today? (No. Earth has gone through many climatic shifts in its history, including ice ages and warm periods.) Tell students that they will be looking at global temperature data to investigate how different Earth's climates might be in the future.

2. Discuss the role of uncertainty in the scientific process.

Tell students that science is a process of learning how the world works and that scientists do not know the “right” answers when they start to investigate a question. Tell students they can see examples of scientists' uncertainty in climate forecasting.

Show the Global Temperature Change Graph from the 1995 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) report. Tell students that this graph shows several different models of forecast temperature changes. Ask: Why is there more variation (a wider spread) between the models at later dates than at closer dates? (There is more variation between the models at later dates than at closer dates because there is more variability in predicting the far future than in predicting the near future.)

Tell students that the ability to better predict near-term events occurs in hurricane and tropical storm forecasting as well. Project The Definition of the National Hurricane Center Track Forecast Cone and show students the “cone of uncertainty” around the track of the storm. Tell students that the cone shows the scientists' uncertainty in the track of the storm, just as the climate models show the scientists' uncertainty in how much Earth's temperature will change in the future. Ask: When are scientists most confident in their predictions? (Scientists are most confident in their predictions when they have a lot of data. This is why the forecast for near-term events is better than forecasts of longer-term events, both in storm forecasting and in climate forecasting.)

Tell students they will be asked questions about the certainty of their predictions and that they should think about what scientific and model-based data are available as they assess their certainty with their answers. Encourage students to discuss the scientific evidence with each other to better assess their level of certainty with their predictions.

3. Have students launch the Earth's Changing Climates interactive.

Provide students with the link to the Earth's Changing Climates interactive. Divide students into groups of two or three, with two being the ideal grouping to allow students to share computer work stations. Tell students they will be working through a series of pages of data with questions related to the data. Ask students to work through the activity in their groups, discussing and responding to questions as they go.

Note: Teachers can access the Answer Key for students' questions—and save students' data for online grading—through a free registration on the High-Adventure Science portal page.

4. Have students discuss what they learned in the activity.

After students have completed the activity, bring the groups back together and lead a discussion focusing on the questions below. Show the graphs on page 7 of the activity. Point out the different time scales represented on the two graphs. Ask:

- Why don't you see the temperature trend from the first graph (1880-2010) represented on the second graph (Vostok ice core)? (The first graph shows a shorter time period (130 years) than the Vostok ice core graph [400,000 years]. The longer-term graph smooths out the short-term fluctuations while showing the longer-term temperature trend.)

- How are ice ages represented on the Vostok ice core graph? (Ice ages [glacial periods] are shown when the temperature is low.)

- What is the average temperature difference between glacial and interglacial periods? (The average temperature difference is 10 degrees Celsius [16 degrees Fahrenheit].)

- How long (in thousands of years) did it take to go from glacial periods to interglacial periods? (The warming happens very quickly, within about five thousand years.)

- How do these changes compare to the time scale for the most recent (current) warming trend? (The current warming appears to be happening much faster.)

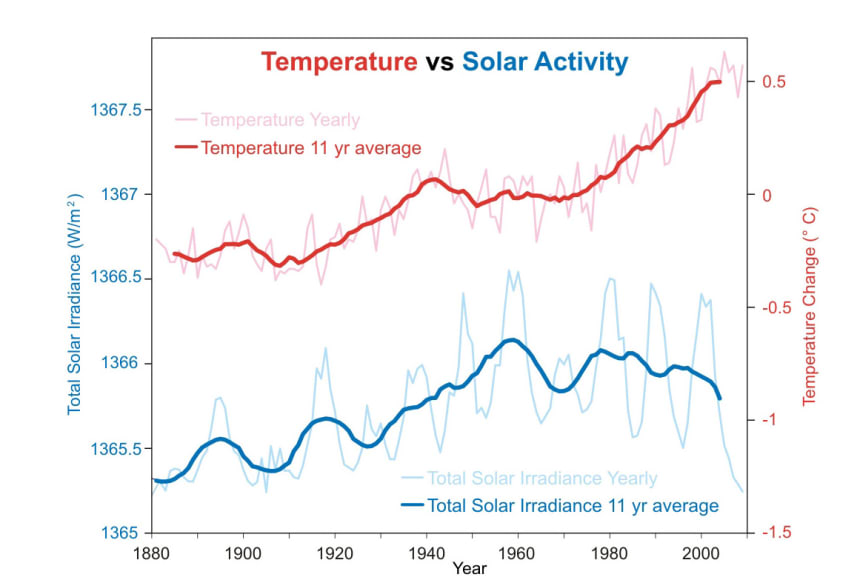

- Why do you think scientists think the warming of the 20th century cannot be explained by the natural variability seen over geologic time? (The warming is happening quickly, and it is occurring in synchrony with increased levels of carbon dioxide.)

Informal Assessment

1. Check students' comprehension by asking them the following questions:

- How has Earth's average temperature changed over the past 400,000 years

- How do scientists determine what the temperature was 400,000 years ago

- What makes scientists more confident in their predictions of future climates?

2. Use the answer key to check students' answers on embedded assessments.

Tips and Modifications

- To save your students' data for grading online, register your class for free at the High-Adventure Science portal page.

- This activity may be used individually or in groups of two or three students. It may also be modified for a whole-class format. If using as a whole-class activity, use an LCD projector or interactive whiteboard to project the activity. Turn embedded questions into class discussions. Uncertainty items allow for classroom debates over the evidence.

Connections to National Standards, Principles, and Practices National Science Education Standards

Common Core State Standards for English Language Arts & Literacy

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Craft and Structure, RST.11-12.4

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.9-10.1

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Craft and Structure, RST.9-10.4

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.6-8.1

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.11-12.1

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.11-12.3

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Craft and Structure, RST.6-8.4

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.9-10.3

- Reading Standards for Literacy in Science and Technical Subjects 6-12: Key Ideas and Details, RST.6-8.3

ISTE Standards for Students (ISTE Standards*S)

- Standard 3: Research and Information Fluency

- Standard 4: Critical Thinking, Problem Solving, and Decision Making

Next Generation Science Standards