The ability to transport goods and human beings efficiently is fundamental to economic life in modern societies. A brief look at the early United States illustrates this principle dramatically. In the first half of the 19th century, Americans built a strong transportation network. These investments in infrastructure were often described as "internal improvements" in the political debate of the time. Improving technology and impressive feats of engineering rapidly transformed the North American continent. Overland roads, canals, and railways greatly expanded economic opportunities.

During the colonial and revolutionary periods, most of the nonindigenous population of North America lived near the Atlantic coast. Eighteenth-century America depended chiefly on water transportation to link small-scale farming and artisan industry with transatlantic trade. Farmers living near the Hudson River or other river systems could float their crops downstream to the port cities. Upstream travel was slow and difficult. Post roads between the colonies had been built by the mid-1700s, but were unsuitable for commercial transport. As a rule, the movement of agricultural produce and other goods was costly. It also took a great deal of time.

Paving the Way for Regional Commerce

In 1794, a new road opened between Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. It was the country's first toll road, built by a private corporation, which was chartered by the state. Soon other groups of merchants were incorporating to pave more turnpikes, especially in the northeast. By the early 1820s, thousands of kilometers of graded paths crisscrossed the region. The toll roads usually failed to turn a profit for their investors, but they provided a major boost to regional commerce. The federal government paid for one major highway during this era. It extended westward from Cumberland, Maryland, at the headwaters of the Potomac River. The Army Corps of Engineers began building the Cumberland Road in 1811. By 1818, it had crossed the Appalachian Mountains and reached Wheeling, Virginia, permitting overland travel between the Potomac and Ohio rivers.

Waterways Connect Rivers and Lakes

Canals gave the system waterways still greater reach. The largest and most important was the Erie Canal. It was approved by the New York State legislature in 1817 and completed eight years later. It extended from Buffalo to Albany at a width of 12.1 meters (40 feet) on the top and a depth of 1.2 meters (four feet). This mighty engineering feat created an artificial waterway connecting the Great Lakes to the Hudson River. The Hudson, in turn, empties into the Atlantic Ocean. The Erie Canal drastically reduced both the travel time and the cost of shipping commodities such as grain and lumber from the Midwest to the eastern seaboard. It led to an immediate and dramatic increase in the shipment of such goods, and the state's investment in the project paid off handsomely. By the 1840s, New York City had become the nation's leading commercial port. It was also well established as the country's financial and trade capital. Other cities along the canal route, such as Rochester and Syracuse, also prospered.

Other state governments hoped to copy New York's success. It led to a furious round of publicly financed canal projects. By 1840, the United States had dug more than 4,828 kilometers (3,000 miles) of canals. Both Ohio and Indiana built their own canal systems connecting the Ohio River to Lake Erie. The Illinois & Michigan Canal, completed in 1848, established a water link between the Mississippi River Valley and the Great Lakes. It spurred the city of Chicago, Illinois, to become the great transport hub of the Midwest.

Trains Transport Goods across the Country

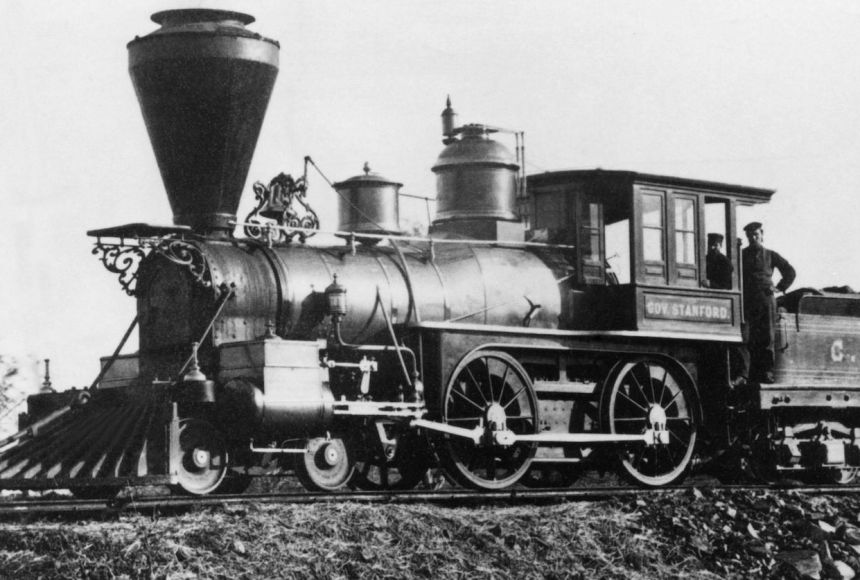

The steam-powered locomotive ultimately had the furthest-reaching impact. Trains were a heavy-duty, fast, year-round transport solution. In time, they became the preferred option for commercial shipping. The earliest U.S. railroads covered only short distances, providing portage between waterways. In 1827, a group of Baltimore, Maryland, businessmen formed a corporation to build the first major railway between their city and the Ohio River. Many more private railway enterprises followed in the decades prior to the Civil War. Between 1840 and 1860, the nation saw a ten-fold increase in the amount of track laid, from 4,828 to 48,280 kilometers (3,000 to 30,000 miles). The majority of this development was in the northern states. The first transcontinental line was established in 1869. Once its infrastructure was completed, the railways lowered the cost of transporting many kinds of goods. Railroads themselves became a major industry.

Productivity Rises

These advances in travel and transport helped drive settlement in the western regions of North America. They were also integral to the nation's industrialization. The development of steamboats and the canal system made it possible for farmers to settle in the fertile lands of the Midwest and Southwest. Constantly improving transport systems gave them an efficient and relatively inexpensive means to deliver their goods to market. The resulting growth in productivity was staggering. Between 1829 and 1841, for example, the amount of wheat delivered along the Erie Canal rose from 3,640 bushels to one million bushels. Busy transport links stimulated the growth of cities, especially New York and Chicago, but also strategically located towns such as Buffalo; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and St. Louis, Missouri. The transportation system helped to build an industrial economy on a national scale.