Medieval mapmakers supposedly inscribed the phrase “Here Be Dragons” on maps showing unknown regions of the world. Unfortunately, however, it appears that, apart from an inscription on a single, 16th-century globe, this claim is unfounded.

Although there were no dragons, and the inscription “Here Be Dragons” was virtually never used, some of the (purported) earliest mapmakers did have to deal with real and formidable megafauna. Their maps date back to the Paleolithic Period, when woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primogenius) roamed Earth along with ancient hominins who lived during the Stone Age (at least 2.5 million to about 12,000 years ago). More recent mapmakers, like the Babylonians, did tell of mythical beasts in their maps, and the ancient Greeks traveled the world they knew in the spirit of cartography.

Mammoth Ivory Maps

The woolly mammoth was a relative of the elephant that lived on the steppes and tundra of North America and Eurasia from around 300,000 years ago to around 3,700 years ago. To humans living in the Ice Age, mammoths were a significant source of meat. In addition, their bones were used to build huts and their tusks were used to make tools and figurines. In at least a couple instances, the tusks of mammoths were used to create what archaeologists have interpreted as maps.

In fact, what is believed to be the oldest map ever discovered is a set of engravings on a mammoth tusk dating from around 25,000 years ago. The tusk was found in 1962 in Pavlov in the Moravian region of modern-day Czech Republic. The tusk includes engravings apparently representing a mountain, a river, valleys, and trails around what is now the town.

Another engraved mammoth tusk was found in 1965 in Mezhyrich, Ukraine, and shows huts along a river.

Abauntz Map

Mammoth tusks were not the only medium believed to have been used by Stone Age humans to make maps. The European Magdalenian culture—dating from 11,000–17,000 years ago—appears to have etched a map onto a stone tablet. The tablet is only a few centimeters across and was found in a cave in Abauntz, in the Navarra region of northeast Spain. The tablet has been dated to around 13,500 years ago.

The engraving illustrates a landscape, including rivers, mountains, ponds, and pathways. In addition, herds of ibex are depicted. It has been interpreted as a simple map, possibly showing a past hunt or a plan for a future one.

The Çatalhöyük Map

Several thousand years after the mammoth ivory maps and the Abauntz map, humans were making maps on the walls of buildings. In the southern Anatolian Plateau in modern Turkey are the two tells (human-made mounds) of Çatalhöyük. It is the site of a Neolithic village: the eastern mound dates between 7400 and 6200 B.C.E., while the western mound dates between 6200 and 5200 B.C.E. The site was the subject of detailed excavations in the early 1960s and is still being excavated.

Of particular interest to cartographers is a three-meter (10-foot) wide mural found on a wall in the eastern mound, dating from around 6600 B.C.E. The lower half of the mural shows tightly packed “cells” thought to represent a village, while the upper half depicts mountain peaks and dark spots that could indicate a volcano.

Other archaeologists disagree with this map-like interpretation, arguing the upper shape is merely a leopard skin and not a volcano. In support of their argument, they pointed out that there was no evidence of a nearby volcanic eruption. Consequently, they argue, the mural is not a map at all, but merely decorative.

A recent study determined that the nearby Mount Hasan likely erupted around 6900 B.C.E., indicating that it is possible that the spotted object in the mural is indeed a volcano.

Babylonian Maps

Slightly less controversial are maps from the Mesopotamian kingdom of Babylon. The Babylonians produced the first known map of the planet. This map, engraved on a clay tablet, shows Babylon at the center of the world.

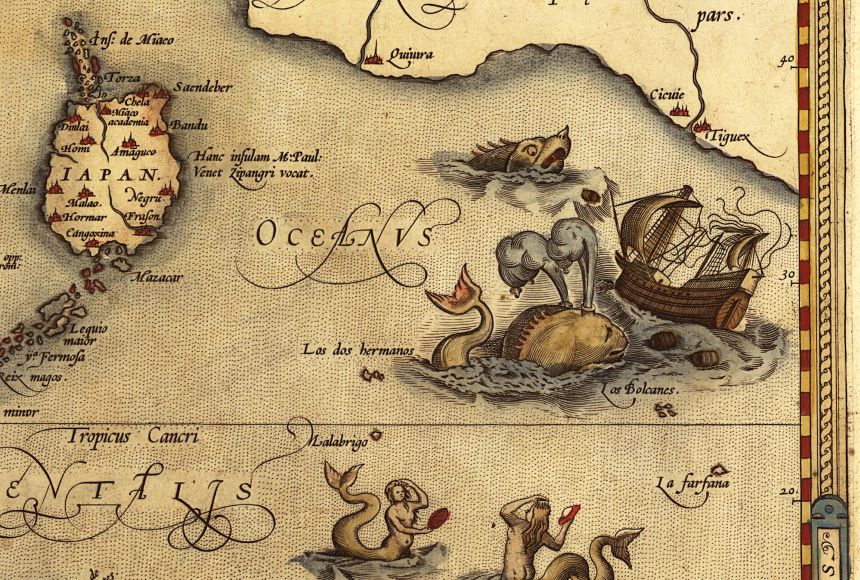

An inscription in cuneiform, an ancient writing system, takes up the top portion of the tablet and describes mythical creatures thought to exist in the depicted regions. Also shown are circles representing cities such as Assyria. A band reading “Salt [or Bitter] Sea” encloses the cities of the map. The Babylonian World Map was intended to be a symbolic rather than literal map. It dates back to around 600 B.C.E.

Ancient Greek Maps

Anaximander of Miletus was a Greek philosopher born around 610 B.C.E. He produced the first map of the world in Greece. Although his map was lost, descriptions and revisions survived: Like the Babylonian map, his map was circular and featured Greece, specifically Delphi, at its center. Europe was on one side, with Asia at the other. The entire world was surrounded by water.

Hecataeus, also of Miletus, lived during the fifth century B.C.E. and improved on Anaximander’s map. He traveled extensively and wrote an account of his travels in Asia, called the Periodos. Hecataeus drew a map (also lost) of the world based on Anaximander’s, which, by examining surviving fragments and texts, historians believe was revised to include details he had learned on his travels.

A few hundred years later, Claudius Ptolemaeus (Claudius Ptolemy, or just Ptolemy), tried his hand at cartography. Ptolemy was a scholar of Greek descent living in Alexandria, Egypt. He lived from around 100 C.E. to around 170 C.E. He is generally considered the inventor of geography—he invented a system of latitude and longitude and invented a way to flatten the planet onto a two-dimensional map.

Maps created using his techniques were generally unknown in Europe until the early 15th century, when his Geography was translated into Latin. At least one map created using Ptolemy’s techniques—which underestimated the circumference of Earth—may have led Christopher Columbus to erroneously believe he could reach Asia by sailing west from Europe.