On April 21, 1865, the train carrying United States President Abraham Lincoln's coffin pulled out of Washington, D.C. In 2015, I retraced its route to his final resting place in Springfield, Illinois.

Early on, I found a railroad spike in the weeds along a section of abandoned tracks. I knew it couldn't date back to the 1860s and it was probably a few decades old. Nonetheless, I kept it in the cupholder of my car for the next 2,414 kilometers (1,500 miles). I liked its look, somehow both industrial and homemade, roughened and angular—Lincolnesque. It reminded me of not just his final journey but also his legacy as the United States' great "railroad president."

In a sense, Lincoln and the new technology had come of age together in the 1830s. It was the first decade of major U.S. railroad construction. As a 27-year-old state legislator, he was already pushing for the construction of new train lines. He later served as an attorney for the Illinois Central Railroad and other companies.

In 1861, when it came time for him to journey to Washington for his first inauguration, Lincoln journeyed by rail through the Midwest and North. He traveled farther to reach the White House than any previous president-elect. Along the way, he made speeches to reassure his fellow Americans that the nation would be saved.

Railroads' Legacy as Nation Builder

But the trip itself also stood as a powerful statement of union. About 48,280 kilometers (30,000 miles) of steel already bound the nation together. It was a sign of the industrial economy that was vaulting the North ahead of the South and of plans to build a railway joining Atlantic to Pacific.

Four years later, the funeral trip was deliberately designed to recall the earlier journey.

During the second day of travel, it crossed the border between Maryland and Pennsylvania. The train rode over tracks that had been used by enslaved people riding the Northern Central Railway to freedom. During the Civil War, trains laden with wounded soldiers often passed here as well.

Part of that stretch still survives. It has recently been repaired for a replica 1860s train, which carries tourists over 16.1 kilometers (10 miles) of track. Hitching a ride aboard the locomotive, I thought of how new and jarring an invention it must still have seemed a century and a half ago.

We chuffed noisily through the stillness of the Pennsylvania fields. We passed an old man with a hoe in a vegetable patch, a gaggle of waving kids, and a teenager holding up his iPad to record video. Our train is history passing by. On a far larger and more intense scale, Lincoln's funeral journey must have felt like this.

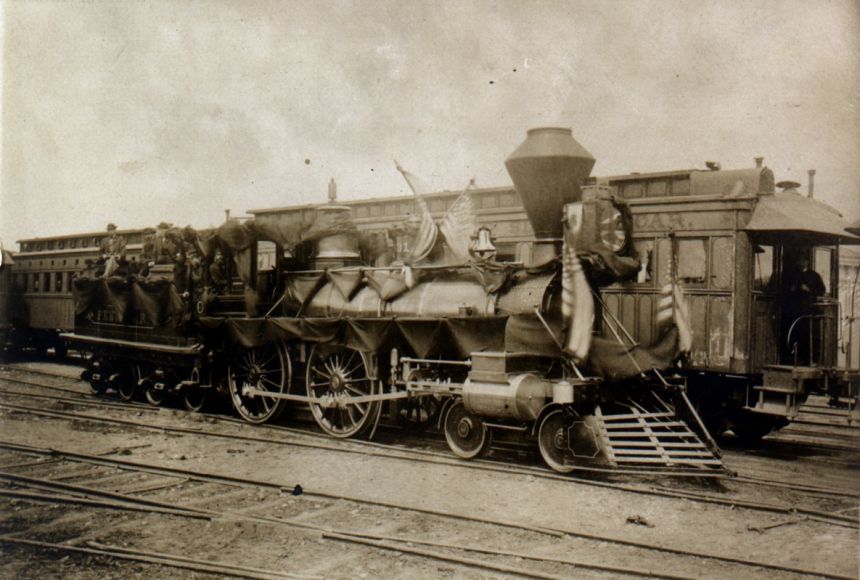

On the 1865 trip, two cars made the entire journey. One of those two was the "officers' car," carrying high-ranking military personnel and members of the Lincoln family, and the other was the funeral car itself. Called the United States, the car had actually been designed to carry the living Lincoln. But in a tragic twist, he rode on it only in death.

Presidential Office on Wheels

The car was finished in February 1865 as a presidential office on wheels. It was a 19th-century version of Air Force One, with elaborately painted and gilded wood and etched glass. For the funeral trip, it was draped inside and out in heavy black cloth fringed with silver. The United States also carried the body of Willie Lincoln, the third son of President Lincoln and Mary Todd Lincoln. Willie had died in Washington in 1862, age 11, and was to be reburied alongside his father.

The train passed through towns and villages, usually in darkness. "As we sped over the rails at night, the scene was the most pathetic ever witnessed," wrote one passenger. "At every crossroads, the glare of innumerable torches illuminated the whole population from age to infancy kneeling on the ground, and their clergymen leading in prayers and hymns."

Especially in the rural Midwest, ordinary Americans felt a connection with Lincoln. Like him, they had suffered the agonies and triumphs of four years of war. This emotional journey was bound up with memories of the railroad too. It was at the local depots that many had caught their last glimpses of sons and brothers who would never return. It was here that civilians brought the bandages, clothing, food, and flags for the war effort. It was here that the first news of defeats and losses arrived, carried by the telegraph lines that ran along the tracks.

Both the telegraph and the train are now gone from most of the rural Midwest. Many local lines closed in the late 20th century because of competition from interstate highways. Many old villages that grew up around rural depots are now dwindling as well. The train yards where bonfires blazed in April 1865 are now parking lots edged by rusting grain silos.

In Elgin, Illinois, I met David Kloke, the master mechanic who built Steam Into History's replica locomotive. He was now completing a full-scale version of the funeral car. The original burned in a prairie fire in 1911, but Kloke studied the original photographs. He tracked down a few scattered fragments of wooden trim and analyzed the paint to reveal the original colors. "It's going to be beautiful, a dark maroon, almost chocolate color, with gold leaf," he told me.

On May 2, 2015, Kloke's United States was in Springfield for a reenactment of the Lincoln funeral. A coffin—empty, of course—would be unloaded onto a horse-drawn hearse and driven to the old Illinois State House for an all-night vigil. It would be taken to Oak Ridge Cemetery the next day. As in 1865, the last few kilometers of the homeward journey was by animal power, not steam. But the ghostly presence of the railroad, like that of the murdered president, hovered close at hand.