What was life like in the earliest cities created by humankind? Historians and archaeologists have pondered this question for centuries. With modern technology, scientific explorers have been able to gain significant insights. Looking at one early civilization, the Indus Valley Civilization, offers insights about early urban life.

An Egyptian and Mesopotamian Contemporary

The Indus Valley civilization (3300–1700 B.C.E.) is also known as the Harappan civilization. It was one of the earliest urban civilizations in the world, roughly contemporaneous with the civilizations of ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, and China. It was located in what is now Pakistan and northwest India, along the flood plain of the Indus River.

Although the Harappans had a written language, the Indus Script remains undeciphered. Most of what is known about their culture and civilization comes from the ruins of their two largest cities: Harappa and Mohenjo-daro. Both cities cover less than 2.6 square kilometers (one square mile). (To compare their size to modern-day cities, Central Park in New York City, United States, is larger than the Harappan cities, with an area of 1.32 square miles.) Mohenjo-daro had an estimated population of around 40,000, and Harappa was probably similar in population size.

The Harappan cities did not have palaces or temples, and there is no evidence they were ruled by hereditary monarchs like kings and queens. Elected officials or other elites may have acted as rulers.

The cities, located about 644 kilometers (400 miles) from one another, were similar in layout. Each city was laid out in a grid-like pattern, with important buildings placed on a north-south axis. Each city had a citadel mound complex with public buildings, as well as a lower town for personal residences.

The citadel mound complex at Mohenjo-daro was about twice as long as it was wide. A wall and brick towers served as fortifications against floods and, possibly, invasion. The citadel complex included the Great Bath, as well as a granary—to store grain—housing, and assembly buildings. The Great Bath, which was made watertight through sophisticated construction techniques, was apparently used for ritual bathing.

One significant feature of Harappan cities was their sophisticated water supply and waste removal systems. In Mohenjo-daro, approximately 700 wells supplied water to both public and private facilities.

Most houses in the lower town had private bathrooms and many also had wells. The bathrooms were typically built against the outside wall of a house. Because of this architectural arrangement, baths and toilets could discharge waste into the municipal sewage network. The network included sewers built underneath the streets. Sewers had removable covers, which allowed workers to clean them with ease. Cesspits enabled the disposal of waste that had to traverse long distances.

Harappan houses, which were usually constructed from bricks, ranged in size from single-room structures to larger, multistory houses. In addition to personal residences, the lower town housed workshops for artisans, such as dyers and potters. In some cases, workshops were part of residential areas, but in others they were located in separate working districts. Harappan bricks were sun-dried and burned. A standardized brick was used across several cities, suggesting some degree of centralized governance.

Wheat, barley, and rice were staples of the Harappan diet. The Harappans also grew and ate a variety of vegetables and fruits. Cattle, chickens, and other animals, including some wild animals, provided meat. Seafood was also consumed.

Harappans used clay or terra-cotta pots, bowls, and other vessels for cooking and storing food. Some vessels were handmade, but others were manufactured with a pottery wheel. Additionally, the Harappans made cookwares from copper and bronze. These artifacts indicate that the Harappans were skilled metal-workers.

An Advanced Culture

One of the most significant discoveries from Mohenjo-daro is a 10-centimeter (four-inch)-tall bronze sculpture of a dancing girl. The sculpture depicts a girl wearing arm jewelry. Her right hand is placed on her hip, and her left leg thrusts forward. The sculpture is considered significant not only because it demonstrates the skill of Harappan metal-workers, but also because it indicates that dance was a form of art or entertainment in Harappan culture. Games and toys have also been discovered in the Harappan ruins.

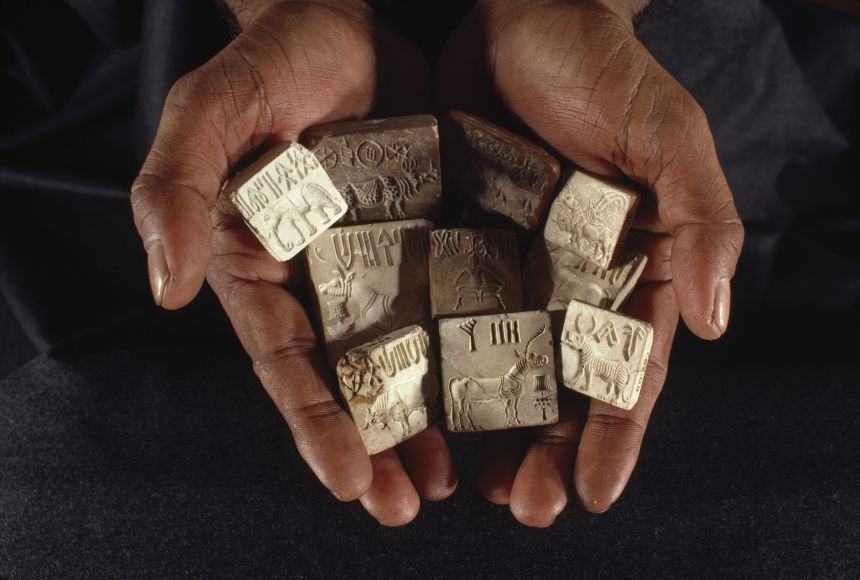

Seals or emblems made from steatite, a form of a mineral called talc, are among the most commonly found Harappan artifacts. The seals featured images of animals or other decorations. They were likely used by merchants to identify packages and verify their authenticity. One famous seal depicts the god Pashupati. This may have been an early representation of the Hindu god Shiva, a principal deity known as "The Destroyer."

Some Indus Valley seals have been found in Mesopotamia, indicating that trade was economically important for the cities. The Indus Valley civilization was part of a trading network that also included Afghanistan, Iran, and Oman. Perhaps because of these trading networks, the Harappans were among the first civilizations to develop a system of standardized weights and measurements. It is possible that the system was used for trade and determining taxes.

Archaeologists continue to investigate the Harappan civilization, and excavations, since 1986, have resulted in many important discoveries. Artifacts are displayed at the National Museum in New Delhi, India, and museums throughout the world.