In Nepal, Mount Everest is known as “Sagarmatha,” meaning “forehead in the sky.” Standing at 8,849 meters (29,032 feet), it is the highest mountain above sea level in the world. Everest is part of the Himalaya, which spans 2,400 kilometers (1,500 miles) and runs through six countries in Asia.

Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay were the first people known to reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1953. It was a death-defying feat of endurance that captured the world’s imagination. Since then, thousands of visitors have flocked to the mountain, and it is starting to take its toll. Today, Everest is so overcrowded and full of trash that it has been called the “world’s highest garbage dump.”

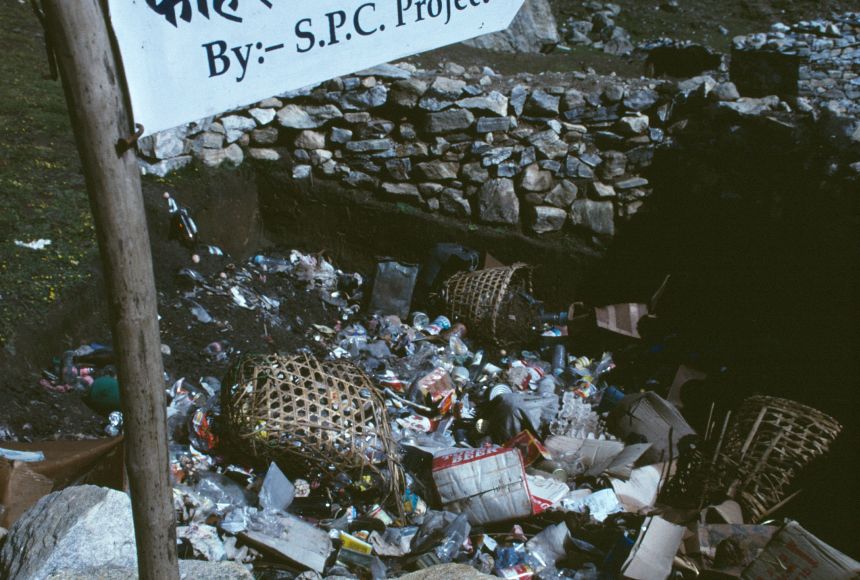

The World’s Highest Garbage Dump

Sagarmatha National Park was created in 1976 to protect the mountain and its wildlife, and it became a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage site in 1979. The park receives around 100,000 visitors each year, and all those people place a strain on the natural environment. Deforestation plagues the local area, as people fell trees to make lodges and firewood for tourists. During peak season, the park receives as many as 500 people per day making the hike to Base Camp, and the intense volume of visitors is eroding footpaths. But the biggest problem is on the mountain itself.

Over 600 people attempt to summit Mount Everest every climbing season during the few weeks of the year when weather conditions are just right. In addition, for every climber there is at least one local worker who cooks, carries equipment, and guides the expedition. The mountain has become so overcrowded that oftentimes climbers have to stand in line for hours in freezing cold conditions to reach the top, where the air is so thin an oxygen mask is needed to breathe. They walk single file at a snail’s pace over the Hillary Step, the last obstacle before the summit. When climbers finally reach the summit, there is barely room to stand because of overcrowding.

Each of those climbers spends weeks on the mountain, adjusting to the altitude at a series of camps before advancing to the summit. During that time, each person generates, on average, around eight kilograms (18 pounds) of trash, and the majority of this waste gets left on the mountain. The slopes are littered with discarded empty oxygen canisters, abandoned tents, food containers, and even human feces. At Base Camp, there are tented toilets with large collection barrels that can be carried away and emptied. But that is where the toilet facilities end. For the rest of their expedition, climbers have to relieve themselves on the mountain.

No one knows exactly how much waste is on the mountain, but it is in the tons. Litter is spilling out of glaciers, and camps are overflowing with piles of human waste. Climate change is causing snow and ice to melt, exposing even more garbage that has been covered for decades. All that waste is trashing the natural environment, and it poses a serious health risk to everyone who lives in the Everest watershed.

The Sagarmatha National Park watershed is an important water source for thousands of people living in communities surrounding Mount Everest. The watershed includes the land that directs rainfall and snowmelt from the mountains into streams and rivers. There are no waste management or sanitation facilities in the area, so garbage and sewage are emptied into big pits just outside of local villages, where they wash into waterways during the monsoon season. The local watershed has become contaminated, which could be incredibly dangerous to the health of the local people. Water contaminated with fecal matter is known to cause the spread of deadly waterborne diseases such as cholera and hepatitis A.

What Goes Up Must Come Down

Both governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have attempted—and are attempting—to clean up the mess on Mount Everest. In 2019, the Nepali government launched a campaign to clear 10,000 kilograms (22,000 pounds) of trash from the mountain. They also started a deposit initiative, which has been running since 2014. Anyone visiting Mount Everest has to pay a $4,000 deposit, and the money is refunded if the person returns with eight kilograms (18 pounds) of garbage—the avegae amount that a single person produces during the climb.

It is not just local authorities trying to make a difference. For years, the Sagarmatha Pollution Control Committee (SPCC) has been working tirelessly to keep the region clean. The SPCC is an NGO and nonprofit run by local Sherpa people. They manage waste in the area surrounding Mount Everest, ensure that people have legal permission to climb, and educate visitors on taking care of the environment.

The Mount Everest Biogas Project is also working to find a long-term, sustainable solution to the area’s sanitation problem. They have plans to build a solar-powered system that would turn human waste into fuel for the local communities. According to the project’s website, this would stop human feces from being dumped at local villages, which would reduce the risk of water contamination and create more local jobs.

Since Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay reached the summit in 1953, over 4,000 people have followed in their footsteps, and hundreds more attempt the climb each season. Some people have argued that the Nepali government should have stricter rules about how many people can try to climb Mount Everest each year, but Nepal relies on the income that the climbers bring to the area. In Nepal, one in four people live below the poverty line, and climbing permits generate millions of dollars of revenue for the local economy. Visitors to the park also generate jobs and income for local people who provide accommodation or work as porters and guides.

Hope for the Future

In the Tibetan language, Mount Everest is called “Chomolungma” (“Qomolangma” in Chinese), which means “goddess mother of the world.” To the Sherpa people, the mountain is a sacred place, deserving of dignity and respect. This was once a pristine landscape, but hordes of climbers and poor waste management have turned it into a polluted mess. However, there is hope that organizations like the SPCC and the Mount Everest Biogas Project, with the help of climbers and the Nepali government, can restore the world’s highest peak to its former glory.